“Spec Ops: The Line” is a title that came out in the slow-churning furnace of mid-summer, singled out as a point of reference in its ephemeral release period and greeted with a consensual, though mild applause. The community’s response mirrored the shy reply that eccentric, heterodox or otherwise intellectual games garner, usually before a sufficient passing of time leads to a less compromised validation and subsequent rise to cult status. “The Line” got a sympathetic look that felt muted by the ever-looming fears of public reproval given the game’s lack of conventional appeal. Since magazines and sites survive thanks to their role as buying-lists, when journalists find off-beat titles they seek an equilibrium between honest criticism and cynic consumer reporting, muddling the two in their texts, so as to remain as balanced and unanimous as possible. Take Edge for instance, its online review opened with this paragraph:

“This could well be one of the most subversive shooters yet made. Nonetheless, Spec Ops: The Line deploys the crude ordnance of thirdperson carnage to persecute more formidable targets: war, soldiering, American interventionism, and the depiction of those things within videogames. A game that understands its own ugliness and base urges, undermining the thirdperson shooter even as it adheres to its formula.”

Other outlets followed a similar line or reasoning: “a game rife with contrast, an utterly commonplace third-person shooter, but narratively, it strives to raise philosophical questions and put you outside of your comfort zone” [Gamespot], “trying to have it both ways, – Gears-flavoured stop-and-pop action one minute, The horror, the horror, the next – but the end result is interesting in its internal conflicts, and bold in its willingness to embrace its own confusion” [Eurogamer]. After the almost art-criticism, comes the consumer angle, bent on addressing entertainment ‘value’. Edge claims that shooting lacks a gimmick to make it interesting (read ‘fun’); Gamespot mentions issues of imperfect movement, meaning control was not satisfying to play; and most reviews mention trial and error grinding and a lackluster multiplayer.

The point here is that though the game was undervalued from a consumer angle, it was acclaimed in terms of its cultural value, at least by the most successful opinion-makers in the community: “A striking vision of a devastated Dubai plays host to murky morality and banal gunplay in Spec Ops: The Line” [Gamespot], or “The first shot has been fired in the battle for a smarter, morally cognisant shooter” [Edge]. More even, those critics that do not need to abide by commercial strains began to dissect the game profusely, and albeit some being more positive than others in their analysis, a strong sense of respect for the game and its aims – as a shining new example of rhetoric on war and war-games – is felt through and through [see Critical Distance for a nice sum-up on the various articles]. Brendan Keogh is writing an entire book on the subject [you can buy it here, and read a meaty excerpt here], his view being that:

“It is a significant game, and that is why I am writing this. (…) So what follows is not a defense of The Line nor is it a praise of The Line. It is simply a reading. It is an attempt to pick apart this game from start to end to try to understand just how I was so powerfully affected by it. For me, The Line made me question just what my responsibility is as a player of military shooters, and the following chapters are an exploration of how it made me ask those questions.”

It is based on this perception of the game, as promulgated by the videogame community, that we expect the game to become a critical reference in the near future (if it isn’t already). What this text aims then, is to vehemently demystify the aura of progressive discourse which has become associated with this title.

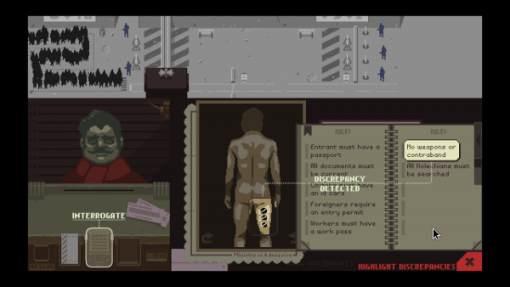

There is no more succinct way of describing the newest iteration of “Spec Ops”, then placing it as an attempt at adapting “Apocalypse Now” into the videogame medium. The game has been officially pegged as a novel translation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”, which is the book Coppola based his operatic war opus on. Conrad’s work has become a seminal, canonic literary work of fiction, one that has gained critical and popular acceptance throughout the twentieth century, being the subject of several works in different media, from radio, theater, film to television and even opera. Why not videogames? However, as far as a translation can go, its formal references and stylistic choices are so influenced and infused with the spirit of Coppola’s interpretation of Conrad’s words that it would be equivocal to claim really as a novel interpretation of the source material. Of the multiple direct references to Coppola’s work, we can include: the backdrop of a war (as opposed to Conrad’s colonialism), several lines copied directly from the film, a similar introduction sequence (see the video), a radioman character whose physical likeness, voice and behavior emulate Hopper’s role (see figure below and video), and most relevant of all, an appropriation of a frantic and hyperbolic tone on the nature of evil, depicted as chaos and madness, which is the iconic trademark of “Apocalypse Now”.

Coppola’s film stood firmly on the wane of the 60’s social revolution and the 70’s depression climate. These decades were a pivotal point in western societies, when idealist notions of peace and love and hope brought a new age with a new utopia for the masses, heralding liberation from orthodox social constraints – family, marriage, work, entertainment and art were all born anew to clash with the old. Sex, drugs and rock-and roll was the mantra of Woodstock, signaling the time when happiness became synonym with pleasureful consumerism. Meanwhile, this hope clashed with a grim realization that the new North-American society lived in constant fear. JFK’s assassination brought the menace of shadow governments and their plots, Watergate showed the true face of corrupt politicians, an oil-driven economic recession incurred in massive unemployment, and the ghost of the ever-looming communist menace of the Cold War always hanged around, all too haunting and oppressive, almost as much as its physical manifestation in the insane Vietnam war… unfathomable in its design, yet absurdly deadly. Reality was fragmented and people were confused, sentiments of freedom and imprisonment, love and war followed quickly in succession. “Apocalypse Now” is, above all, a journey through those decades of dreams and nightmares, as we go from nonsensical drug-fueled euphoria on the battlefield, all surf’s up, pyrotechnics and Playboy bikinis, to a descent into the heart of darkness of the jungle, where war and cruelty become real, now borne into the flesh of Col. Kurtz’ monstrosities. “The Line”, especially in its narrative layer, follows these coordinates, simply propelling similar feelings of hope and anxiety to our present, addressing 9/11, Iraq, the complexities of a post-modern world at war, and how the new digital hedonist culture perceives this.

Conrad’s book, however, presented a voyage to the darkness of the human soul during the age of colonialism; it was a sailor’s mournful and poetic reflection on how European empires were built, and how civilization was brutally imposed on barbaric lands, an act of savagery as great as the savagery it meant to domesticate. Nature was the true darkness, both the nature that lives in its rawest, purest form in the untamed jungle, as the nature that lives in Man’s heart, always waiting to come out and spray all forms of aggression and destruction. Few of these elements have direct connections with the “The Line”, which presents its “Heart of Darkness” as an LSD trip to a middle-eastern war, nightmare and dream shot with black humor, rock music and cynicism galore. This is “Apocalypse Now” brought to the XXIst century. If any more evidence were needed that the game is trying to revel in the spirit of the film, we have only to dissect the licensed soundtrack that evokes the iconic rock bands of the Seventies – exchanging “Apocalypse Now’s” Beach Boys, Rolling Stones and Doors for the likes of Hendrix, Deep Purple and Martha Reeves – and adding the ephemeral taste of erudition with a hint of opera – so where once was Wagner’s “Walkürenritt” (Ride of the Valkyries) from “Der Ring des Nibelungen” (The Ring of the Nibelung), we now have the proxy of Wagner’s Italian nemesis, Giuseppe Verdi, with “Messa da Requiem’s” (Requiem Mass) “Dies Irae” (Day of Wrath), coincidentally, one of Verdi’s most feverish and bellicose excerpts of music. Once established that the game is really adapting “Apocalypse Now”, and that “Heart of Darkness” is an incidental reference (perhaps so for matters of authorial rights and licensing costs) a more accurate interpretation of the work can ensue. But this is not to say that there are no direct bridges to the book, only that these are few and usually insubstantial; take for instance the renaming of Kurtz to Konrad, K stems from Kurtz and Conrad from Joseph Conrad, of course, a weak pun that is nonetheless symbolic of the relevance of Conrad’s name for the game.

Beyond formal considerations, and strictly thematically, “Spec Ops The Line” is still about a “Heart of Darkness”. Only the darkness here is one far more conventional, a sort of down-to-earth interpretation of “Apocalypse Now”, with none of the ambiguity, existential profundity and far-reaching considerations of the works the game bases itself on. “The Line” deals with that murky line that separates high morals from base human behavior, and how war strains the tension and inner contradictions between human’s predatory animal behavior and our highly intellectualized aspirations of empathy and communion. The story follows Captain Walker, a self-righteous officer of a Delta Force unit in a Dubai war, on a mission to investigate the dealings of a rogue battalion led by the charismatic leader Coronel Konrad. Apparently seeking to solve the humanitarian crises of famine and thirst provoked by unrelenting sand-storms and the onslaught of war, Konrad established a despotic rule driven by brutal force and uncompromising law, a new society where survival is uphold by the harshest of contingencies, and where trespassing is dealt with torture and death. Despite the army’s brutality being meant to safeguard human life against the gruesome rule of Nature (both the environmental and the human, as per Conrad), civilians start to amass in violent militias seeking to overthrow the army’s impromptu government and restore freedom. Complicating matters further, it also happens that this rebellion and armed by CIA operatives who have vested interests in seeing no witnesses of the war remain alive, lest news of human rights violation and the horrors of the war reach the outside world. In the midst of this Palestinian-sized disaster, Walker finds himself the target of both factions, seeking to understand how the war came to be, and trying to save what’s left of the refugees. It doesn’t go very well, as he is soon forced to face choices that defy all ethic boundaries. At these points the game mixes two different narrative set-ups: some of these dilemmas are catch 22’s with no true alternative whilst others are choices between lesser evils. This effect heightens a sense of confusion that lies at the heart of the captain’s role, as well as the haziness of the distinction between good and evil in a context where death hangs at the balance of every split-second decision.

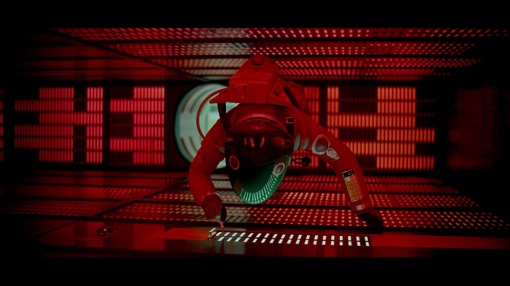

The third act of the game reveals new light over the proceedings in the Dubai war, with several surprise reveals in the form of hallucinatory sequences. In these, Walker is confronted with the horrors of war, combating the ghosts of those he killed and watching the gates of hell open before him [see the Sauron-like imagery of hell in the picture above]. The final stretch in the game also sees the act of killing made truly violent from the perspective of Walker: what had hitherto been natural murders for a jar-head, suddenly become remorseful acts of spite and vengeance, both towards himself and his opponents, all turned to cogs in a perpetual machine of death. He rants and blasphemes out loud as he kills in ever more violent ways, for the first time seemingly aware of his condition in a theater of war as an instrument of death, cursing all yet never shirking from the the role that destiny gave him. Whether physical or mental or spiritual, it is pretty clear that Walker is in a personal purgatory. The shift in tone, from realism to the pseudo-surrealist, is based on the interpretation that the entirety of the story-line is supernatural in nature, as one of the creative leads at Yager suggests: this purgatory is diegetic (see the interview).

In the very end, the final horror Walker must face is that he is Coronel Konrad. Konrad was a mirror-figment of his imagination, a creation he conjured to dissociate him from his own atrocious decisions during the war. The idea of Konrad and Walker being the same – as in sharing similar outlooks on the savagery of Nature and the hopeless, inescapable amorality in human living – is a primary part of interpreting the book, and with some nuances, the film (there, Capt. Willard kills the Kurtz-God to avoid becoming completely like him). In “The Line”, we go from a spiritual, symbolic, subtle idea to an extremely literal one, trivialized as a supernatural twist in a psycho-thriller. The peculiar embrace for such an unorthodox mechanism can be attributed to a search for sheer surprise factor, and maybe also even an obligation to reference, out of popular taste, David Fincher and his “Fight Club”, the ultimate icon of post-2000 anarchic visual aesthetics in media. The film’s ending is herein mirrored: there’s the man with split personality where one psyche points the gun at the other (which is the same as pointing it at himself), and there are the surroundings, a high-rise with a view over the city; even the segue is similar, destruction spreading across an urban landscape in a myriad of explosions, all blurred with edgy montage and camera filters. We live in a society that shirks from symbolism, transcending meaning and ambiguity, and where materialism, both physical and fictional and intellectual, is granted precedence over the elusiveness of spirituality. The focus of the grand reveal seems, basically, that Walker being Konrad could not be so subtle to the point of being poorly understood by the game’s audience, and so had to be made a smashing realization of a physical reality – Konrad couldn’t be merely an ideological kin to Walker, he had to be Walker. This, just as the non-figurative interpretation of ‘purgatory’, speaks a lot about who the designers were trying to communicate with and their cultural pot of references (surely not to readers of the novel).

It must be made clear though, that the lack of nuances in the narrative is the least of our concerns, as it is a hallmark of most games. The thornier subject is that “The Line” was created inside an industrial production context, more so, inside a long standing franchise (the original “Spec Ops” is a 1998 tactical war game for the PC), and how that fact impacts the agenda for the game’s interactive experience. We have had little contact with the franchise in the past, but what little we had, with the first Playstation editions of their work, left an appalling impression… not quite the suitable background to adapt either of the two artistic masterpieces that it wishes to base itself upon. Further, both Conrad and Coppola were authors in their own right, having to pay comparatively little attention to commercial needs of producers and distributors (Coppola became famous for this attitude, to the point of costing him the commercial collapse of his Zoetrope studio). We don’t believe there is any authorial vision possible in the realm of “The Line’s” production, given first and foremost that there are no known authors in Yager Interactive to begin with. The Creative Leads of “The Line” are Cory Davis, who also doubles as Design lead, and François Coulon, with narrative in charge of Richard Pearsey and Walt Williams. Their resumes speak for themselves. Coulon worked on many generic games, mostly in production roles, with only a scant note on his curriculum mentioning participation as co-creative director for the first “Splinter Cell”. Cory Davis was in charge of level design in “F.E.A.R. Extraction Point” and “Condemned 2” and had miscellaneous development roles in “F.E.A.R. 2”, and Pearsey worked with him as a writer for “F.E.A.R. Extraction Point” and “F.E.A.R. Perseus Mandate”. Finally, Walt Williams is story editor for 2K games, which includes editing everything from “Bioshock” to “Mafia 2”, though as a writer he only co-penned the unfortunate sequel to “The Darkness”. None of the works created by any of the members of the creative team, are indicative of any visionary author, artist or designer, no matter how repressed and well hidden in the dark, depersonalizing halls of a developing company such as Monolith Productions. You would hardly expect an essay on war from authors whose gameography features an extensive catalog of generic shooters that boast violence and militarism.

2K Games, “Spec Ops: The Line” publisher, is not without its merits as a mega-publisher, having bet on some creative, less standardized titles as “Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth” and even sui-generis AAA titles such as “Bioshock”, but these are specks of sand in a vast sea of published titles with no artistic value. So what we get is a normal publisher intent on making money, hypothetically willing to bend one or two rules of the marketing books, and a creative team whose experience is in standard, by-the-numbers, action games. “Spec Ops” is a brand associated with the tactical shooter genre, games where war is a means to entertainment, and Yager’s background is from “F.E.A.R.”, a game where violence is also a means for entertainment. Were these the right people in the right context for a game that seeks meaningful debate on the subject of war? Doubtful, to say the least. But let us assume that Yager really wanted a mature, artistic game, that posed a provocative and groundbreaking take on the subject – 2K games would never risk a AAA budget on such aspirations. “The Line” got released because it still was, at heart, an entertaining war game with mass appeal, its goal to sell millions.

Which brings us to the inner crux of “Spec Ops The Line” – its genre roots. Whilst we concede its creative pursuit may, hypothetically, have lied in an attempt to convey through the videogame medium similar themes as those in the works it bases itself on, no matter how inconsequently or unpreparedly, the fact remains that the interactive make-up of the game was never conceived to house such preoccupations, for there is no clash with previous shooters, nor is there any true subversion of the team’s previous creations. “The Line” is no better at addressing war than “F.E.A.R.” was. In game design terms, it is, no more, no less than a standard competitive third-person shooter. It inserts itself neatly in a long lineage of the military action genre, a genre whose overtly declared mission is entertaining by providing players a sense of empowerment through annihilation of opposition, gratification by fetishization of war and its props, chaos and destruction and death turned to mere fireworks spectacle. “The Line” is an ipsis verbis refrain of “Gears of War”, a game whose main author is straightforward in his unpretentiousness and rudeness, as well as its Reagan-era rhetoric of hedonist, mindless destruction and obscene brutality. Cliff Bleszinski, at least, is sincere:

“In many ways, I’m a child of the ’80s. I was raised on movies like Predator, Robocop, and even goofy ones like Cobra with Sylvester Stallone or the ones starring Arnold [Schwarzenegger]. I think those types of things represent a time, an era when people just loved that sort of mindless action. If you take a look at a film today like The Expendables—people love that. Gears represents a modern-day feel of that sort of nostalgic time.”

Yager’s work is an almost perfect copyist assignment of that design, with only one small variation– all characters die easily in “Spec Ops” as if to underline human frailty (as opposed to the brawny space-marines of “Gears of War”). This imposes a tenser rhythm to cover-combat, and this high-risk, high penalty flavor results in the grinding trial-and-error that was criticized in some reviews. Apart from that inexpressive detail, there is no subversion of the shooter genre, unless in those rare instances where the game becomes a series of narrative choices. Only in the final moments of the tragedy, when both Walker and his buddies start voicing the horror of war (whilst the player continues the game-loop of carnage), does the visual and aural anger manage to dampen our sense of accomplishment at conquering another opponent. But by the third act, this point goes unheard, lacking the strength to force a reassessment of what is always first and foremost, a cool game about killing cardboard soldiers. It’s laser tag through and through, and no amount of cutscene brooding can force us to reassess that.

So, what we get is a game that is supposed to question the morals of war, that plays out as a normal power fantasy, complete with grand set-pieces of destruction – straight from “Call of Duty”, another game lacking in pretense of seriousness – where there is little, if any, tonal underpinning to question the amorality of it all. More so, players are, again following the genre’s stipulations, commended for their ‘acts of valor’, with slow-motion death-cams heightening gorish outcomes with a snazzy bang, and banal icons of achievements and progress bars flying through the screen, signaling player proficiency in the art of killing opponents with specific guns and techniques. The game tells you that head-shooting your opponents is a goal, and thus morally good, worthy of praise and better when done in a hip way. Where is the subversion? This is Bleszinski’s design drive in a game that claims to wish the exact opposite. “The Line” plays like a game adaptation of “The Expendables”, not “Apocalypse Now”. Of the latter it sees only its explosive satire and glorified violence, failing to re-work its subtleties and sub-text and aesthetics. “The Line” is not a game about war, it is a game that wears the pretense of war, and in its heart just wants to patronizingly entertain an immature audience. For our role as players has not changed, nor has our emotional experience: in “The Line” we remain fashionable killing machines.

The location’s characterization, which has been praised in most reviews, actually further enhances the vapid stylization of violence. Whilst technologically competent, this Dubai never feels like a real war scenario, it is distant and voluptuous and unlike anything in the wild, dense and inscrutable darkness of “Apocalypse Now’s” jungle (inspired by Werzog’s brilliant masterpiece, also a kin to Conrad’s novel, “Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes”). Here we have a dreamscape, a fantastical place where light shines as only possible in a computer screen, all warm reds and digitally-enhanced oranges, textures made to bloom in a soft glow, all as unrealistic and tasteless as a heavy-handed photoshoped photography. Ruins are shiny and the sand lush; the glassy phallic towers of bygone capitalism, though destroyed and falling brick by brick, remain a symbol of the glorious, opulent past and never the dreaded present. It’s another aesthetic non-sequitur: to beautify everything in a game’s visual landscape, whilst portraying the most horrible and visceral of themes in front stage. The stylistic choice is reminiscent of another son of Reagan-era Hollywood violence, Michael Bay, the uneducated MTV-junky with an unhealthy, quasi-sexual fascination with explosions. His signature hot neon-gold hues, ADD edits and slow-motion kill-cams all make an appearance at some point of the game. In this search for digital beautification, the art direction went as far as resorting to lavish art-deco for the destroyed interiors, basically assuming that irrespective of subject or tone, for a game to shine visually it must cite “Bioshock’s” destroyed Rapture.

Another crucial aspect that reinforces this trivialization of violence, lies in a total lack of care in making soldiers and victims seem human, unique, borne with the flame of life, rife with empathy and suffering. You get the same generic looking soldiers that you execute thousands of time in an endless bog of deathly repetition, and as always you play the hard-chinned American hero, buddied with a black negro with a conscience and a redneck racist that keeps spouting patriotic bull. The writing is not Conrad caliber, that is sure, and though the models and animations of the main characters are above average – emoting convincingly for most of the story – the non-playable characters are as forgettable as in any shooter. How are we expected to cry over nameless NPC# 192, when his model is reused over and over and his face is completely covered, with no inkling of a soul in either his eyes or behavior? The formal qualities of how human life and suffering are depicted is symptomatic of a total lack of sensibility to these issues. One of the main scenes of carnage sees the death by phosphorous burning of hundreds of civilians. The game then presents center-piece a burning pietà [above is the in-game depiction, and below is the equally artless painting that Konrad does of the same scene], the image appallingly crude, in a style that evokes more easily horror tropes as expressed in “Fallout” or comic books along the line of “The Walking Dead”. What almost saves these scenes is the sound, which is immensely revolting in of itself, with human screams and flesh sounds so accurate that it almost makes you feel the emotions which the game occasionally wants to achieve. Impeccable voice acting from main actor Nolan North in the role of Walker (a risky cast choice that pans out), also helps establish an emotional gravitas that is otherwise absent, but that is the extent of positive adjectives we can afford in a game whose overt aspirations consistently outshine their execution.

There is a tenuous line separating two very different theses that can explain the purpose and creative pursuit of “Spec Ops the Line”. One states this is a game that is genuinely pursuing a thoughtful discourse on war and human ethics, based on a literary masterpiece. That the actual game misfires and shirks away from this grand vision, is an issue of constraints of the medium, its vocabulary and socio-economic context, which are not prepared for a true breakthrough – this is the view in some critical articles. The alternative we propose, is that those aspects of the artifact which are viewed as interesting and a sign of maturing of the genre, are merely a cynical cover to garner attention and praise, in a game that was never conceived to be anything but a commercial product, dictated by an author-less industrial production machine. This does not invalidate that some parts of “The Line” really are an adolescent attempt at promoting a post-modern discourse on war. Well, perhaps not war itself, but maybe the way our consumerist-hedonist society sees war through videogames: fun-gameplay that fantasizes death as a positive goal, whilst reality is muddy, cruel and immoral. This is possible, but if this last rhetoric point is there, then the game truly is pointless: for it embodies the worst qualities of the artifacts it means to criticize. We don’t need a self-conscious “Gears of War”, we need a game that really criticizes the shooter (aesth)etic by presenting a moral antithesis to “Gears of War”. Videogames desperately need what films about the Vietnam war showed to the North-American psyche – a bleak sense of guilt and conscience and sin. A conscience that war is not a game, that death on massive scales is a catastrophe. There isn’t any progress in taking 80’s action schlock and slamming a hypocritical narrator on top; even “The Expendables” has moments of moral self-awareness, though that still doesn’t mean it is a serious film:

“You remember that time we was up in Bosnia? We took down them Serb bad boys? All our guys were gettin’ chopped up all around us and there was blood everywhere. I never though I was gonna make it out of there and I know you didn’t and you didn’t either. Kinda feelin’ like… dead too, ya know? My heads all very, very black place. Didn’t believe in shit. Just goddamn Dracula black. I remember I got this bottle of this local shit they have over there. That Silvits… I think that’s what it was called. And I ain’t feelin’ no pain now… and I come up on this, uh… I come up on this overland bridge, and I see this… I see this… I see this woman standing there, ya know? And she’s, uh… I stepped out and she saw me, and she’s just lookin’ right… right in my eyes. And I was lookin’ right in her eyes, and I knew what she was gonna do. She looked at me, and I knew she was gonna jump. You know what I did, man? I just turned around I kept walkin’ until I heard that splash and she was gone. [crying]After… after taking all them lives, she was one that I could have saved, but I didn’t, and uh… What I realized later on was, uh, if I’d have saved that woman, I might have… I might have saved what was left of my soul, ya know.”

This has been the generation of military shooters. “Call of Duty” games alone have sold over 120 Million copies since “Modern Warfare” was released, generating billions of dollars in the process. It’s big business and so big in fact, that the entire medium has been coerced by its economical forces to converge into the shooter genre. Similarly themed pieces were produced by the dozens – “Brothers in Arms”, “Killzone”, “Resistance”, etc. – and most of this DNA was incorporated in different genres, from open world games like “GTA IV” to action-adventure pieces such as “Uncharted”. This current in the production scene, through crowding and repetition, had the perverse side-effect of banalizing the formula it chose to promote. The search for flashy new marketing angles became the core of producers preoccupations. “Haze” was one of the first attempts to deal with more adult subject matter (drugs, war, morality), recent “Medal of Honor” games have also tried to become more serious and humane in their portrayals of Middle-Eastern wars, and even “Black Ops” blended conspiratorial 70’s fiction into its Tom Clancy narrative. Meanwhile, “Bioshock” hit a home-run with the notion of a shooter for smart people, a satire of capitalist fanatic Ayn Rand, and “Far Cry 2” made the statement, promulgated by game-designer of the moment, Clint Hocking, of being the ultimate oxymoron: a shooter based on “Heart of Darkness”. When Yager chose Conrad, they were not choosing the hitherto unchosen: they knew the critical praise received by “Far Cry 2” despite its lackluster sales figures, and they knew audiences were starving for ‘adult’ war games. So the end result is “Spec Ops The Line” – a new iteration in a generic military game franchise, from the creative non-authors of F.E.A.R., its gameplay modeled after “Gears of War”, its narrative taken from “Far Cry 2’s” pseudo-subject matter and its visuals reprising formal elements from “Bioshock”. That’s it, this is its creative process laid bare. The theme of war needs to be dealt with authenticity and honesty in the videogame medium, but “The Line” never had these to begin with.

It is nigh impossible to reform a genre from within, especially when its expressive purpose lies in the antipodes of what you want to convey. Just as “The Expendables” can never be a drama about war, “Gears of War” can never be a game about war. Yager was playing with bad references and got nowhere new. Even had they a vision for a dramatic statement on their genre, they had to sell to compensate their AAA budget, and that meant they had to deliver a game that subscribed to popular perceptions of what a war game is: entertaining. As a shooter game, “Spec Ops” is, as most media articles tell you, decent and nothing more. As a cultural artifact, it is one of the most offensive and manipulative titles to have been released in the past decade, for it mystifies its role, leading audiences to consider this is a game with high moral considerations on the nature of war, when it is anything but. In years to come, we run the risk of having players read about and look back seriously at a game that emulates “Call of Duty” as if it were “The Thin Red Line”. Whilst the former is dumb and so offensively so, that no one would ever even consider them to be expressive, the same cannot be said of “The Line”. It implies more than its experience affords, and in a medium with little artistic criticism to speak of, we fear history will look this title with kind eyes. Critics and scholars, while divided, respect “The Line”. Keogh is even writing a book on it, because he feels it made him question how we look at war in videogames. He is right. “Spec Ops” shows that videogames look at war in crass, shallow ways. They tell us that war is fun, they trivialize violence and its consequences, make it pretty and enjoyable, and appeal to our male testosterone, making us feel strong and bullish and powerful. The moral considerations on this expressive rhetoric are self-evident. War is the antithesis of those feelings: it is the suppression of the self face the country-machine, it is anxiety and terror made living constants, hopelessness as the sole possible state of mind and death the only release. “The Line” doesn’t make you feel that way. It is questionable whether or not it even addresses, abstractly, this state of affairs. It may acknowledge it, but it forgoes any chance of redemption by replicating the moral evil it questions. The tenuous line was crossed the moment it made killing ‘fun’. How could this game pose questions on war, if its answers are similar to those of “Gears of War”? The answer is: it can’t.

*Some citations were edited for reading ease, but always respecting the original sources.

Everything most eventually come to an end. Sometimes, it’s an excruciatingly long winding one, as is the case with Metagame. Between my PhD and classes, my newspaper reviews and occasional talks, the book I can never seem to finish writing, and wanting to continue playing these darned horrible videogames, time just slips by. But the past, as they say, is history. The college paper is gone and with it my column, blogs are out-of-fashion, too wordy for the twit generation to read through, and soon I’ll have to find a proper job to make ends meet, which inevitably means an even lesser disposition to write here. And now, on top of all this, I’ve been invited to write for a column in the Portuguese IGN website, which will likely drain all my videogame writing desires. This is not final, I’ll still be around, just don’t expect anything more than the recent paucity.

Everything most eventually come to an end. Sometimes, it’s an excruciatingly long winding one, as is the case with Metagame. Between my PhD and classes, my newspaper reviews and occasional talks, the book I can never seem to finish writing, and wanting to continue playing these darned horrible videogames, time just slips by. But the past, as they say, is history. The college paper is gone and with it my column, blogs are out-of-fashion, too wordy for the twit generation to read through, and soon I’ll have to find a proper job to make ends meet, which inevitably means an even lesser disposition to write here. And now, on top of all this, I’ve been invited to write for a column in the Portuguese IGN website, which will likely drain all my videogame writing desires. This is not final, I’ll still be around, just don’t expect anything more than the recent paucity.